INTO THE HISTORY OF THE DOG WORLD

Last time I wrote about one from my best meet with someone very very importand.

Mr. Mike Morabito start colaborating with us and we have a chance read his great articles about our best friends, about our dogs. The new STILLADOG serie “MORABITO’s WINDOW INTO THE HISTORY OF THE DOG WORLD“

Welcome here between his lines ✨

Dog domestication and the dual dispersal of people and dogsinto the Americas

Domestication, evolution from wolf to dog has always been and still is quite an intersting topic, with this first article i will makea chronology, a time libe of evolution and domestication throughthe milenias until arrive to the actual dogs, and concenstrate of corse in the A.p.b.t., bull & terrier, molosser type dogs, this said, lets begin, hope you’ll enjoy as much as do,this is not by anymeans, a definite article, since science provides always new and different evidence, this article its just to set some basis, but notthe definitive one to show where and when all begun…

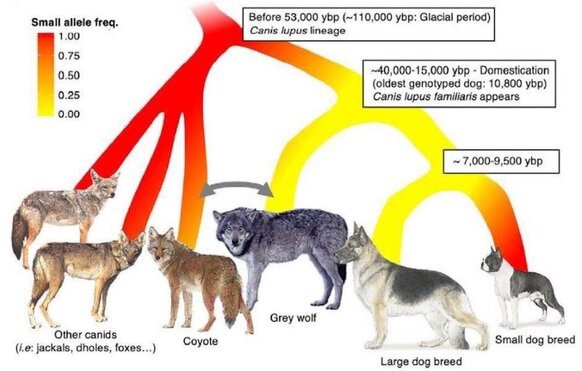

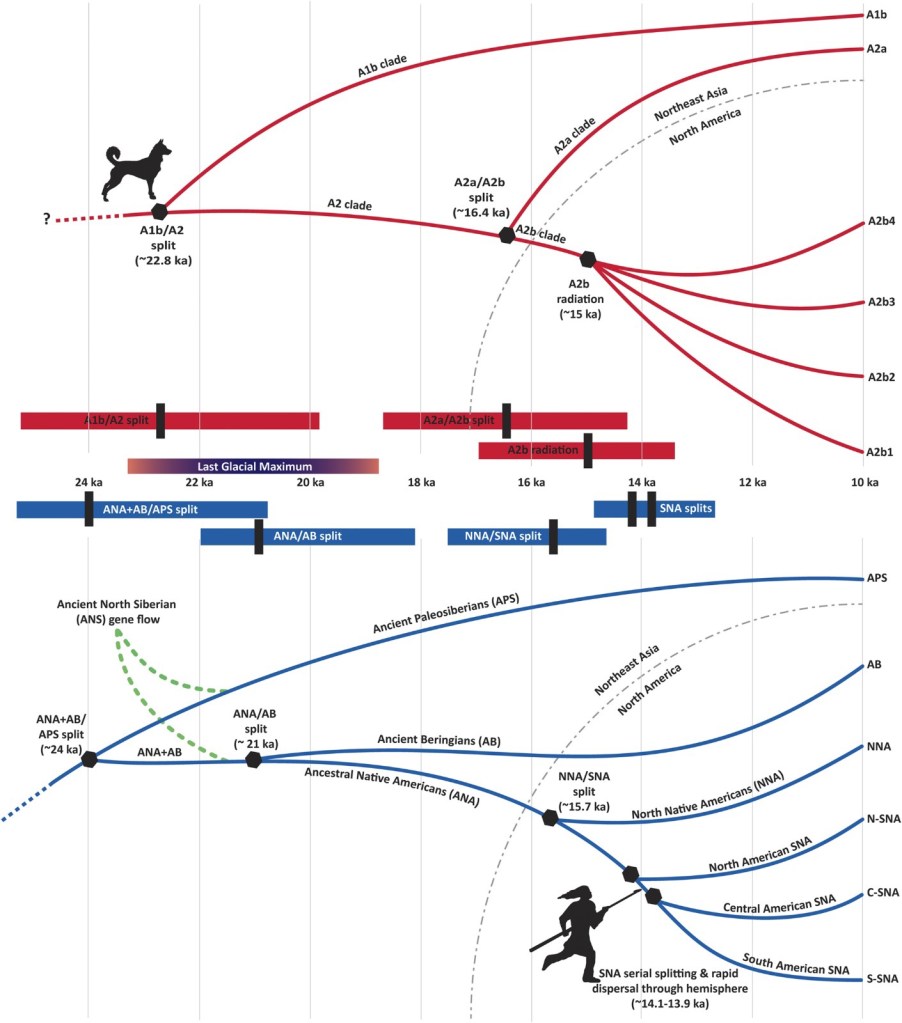

Advances in the isolation and sequencing of ancient DNA havebegun to reveal the population histories of both people and dogs. Over the last 10,000 y, the genetic signatures of ancient dogremains have been linked with known human dispersals in regions such as the Arctic and the remote Pacific. It is suspected, however, that this relationship has a much deeper antiquity, and that the tandem movement of people and dogs may have begunsoon after the domestication of the dog from a gray wolfancestor in the late Pleistocene. Here, by comparing populationgenetic results of humans and dogs from Siberia, Beringia, and North America, we show that there is a close correlation in themovement and divergences of their respective lineages. Thisevidence places constraints on when and where dogdomestication took place. Most significantly, it suggests thatdogs were domesticated in Siberia by ∼23,000 y ago, possiblywhile both people and wolves were isolated during the harshclimate of the Last Glacial Maximum. Dogs then accompaniedthe first people into the Americas and traveled with them as humans rapidly dispersed into the continent beginning ∼15,000 y ago.

Dogs were the first domesticated species and the only animal known to enter into a domestic relationship with people duringthe Pleistocene. Recent genetic analyses of ancient dog remainsand of the archaeological and genetic records of ancient peoplehave demonstrated that the spatiotemporal patterning of specificdog mitochondrial lineages are often correlated with the knowndispersal of human groups at different times and places.

For instance, a study of mitochondrial signatures derived fromancient Near Eastern and European dogs has demonstrated that a specific haplogroup arrived in Europe as dogs dispersed out of the Near East along with farmers. The first dogs to arrive in New Zealand did so with newly arriving Polynesians. People and dogsalso dispersed together in the North American Arctic, wheredogs carrying a specific mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) signature accompanied Paleo-Inuit groups as they moved into the region∼5,000 y ago (5 ka). Subsequently, the arrival of Inuit groupsinto the same region ∼1 ka was accompanied by the introductionof a dog population that carried novel mtDNA signatures.

These correlations between the dispersals of people and specific dog lineages may have begun much earlier, perhaps soon after dogs became domesticated from a gray wolf ancestor in Eurasia, though precisely where and how many times that process took place remains unknown. The archaeologically documented presence of dogs in the Americas by at least 10 ka suggests that dogs accompanied the early human groups who moved from northeast Asia across the Bering Land Bridge (Beringia) into the Americas. On the basis of current archaeological and genetic evidence, this movement likely took place before 15 ka. Here, we take advantage of this record and newly available evidence from humans and dogs in late Pleistocene Siberia, Beringia, and North America to assess the likelihood that the first people to reach and disperse across the Americas did so in tandem with their dogs. This analysis allows us to better understand that dispersal process and present a hypothesis for the temporal and geographic origins of domestic dogs.

The First Dogs

that entered into a domestic relationship with people during the Pleistocene. Second, the specific wolf population from which dogs derived appears to be extinct. Finally, genetic and archaeological evidence from modern and ancient dogs and wolves demonstrates that dog domestication took place in Eurasia. Many other aspects of dog domestication, including the circumstances under which the relationship began, the time frame, and the number and location(s) of potential independent domestication regions, remain unresolved.

The shift in human–wolf interactions that led to domestication has been addressed through a wide variety of approaches, and there are ongoing debates over when the first recognizably domestic dog appeared. The earliest generally accepted dog dates to ∼15 ka (from the site of Bonn-Oberkassel, discussed below). However, claims for the existence of domestic dogs as early as 40 ka have been made on the basis of morphological, isotopic, genetic, and contextual assessments of ancient canid remains. Yet, none of these potential domestication markers is fail-safe, owing to the fact that wolves and early domesticated dogs can be difficult to distinguish from each other.

Numerous archaeometric approaches have been applied to document the interaction between wolves, dogs, and people in order to establish the time frame and geography of dog domestication. These studies have shown, first, that dogs were the earliest animal domesticated, and the only species.

To be continued in a week and it will be more and more scientific, human and canine✨

Mike Morabito

FOR SALE

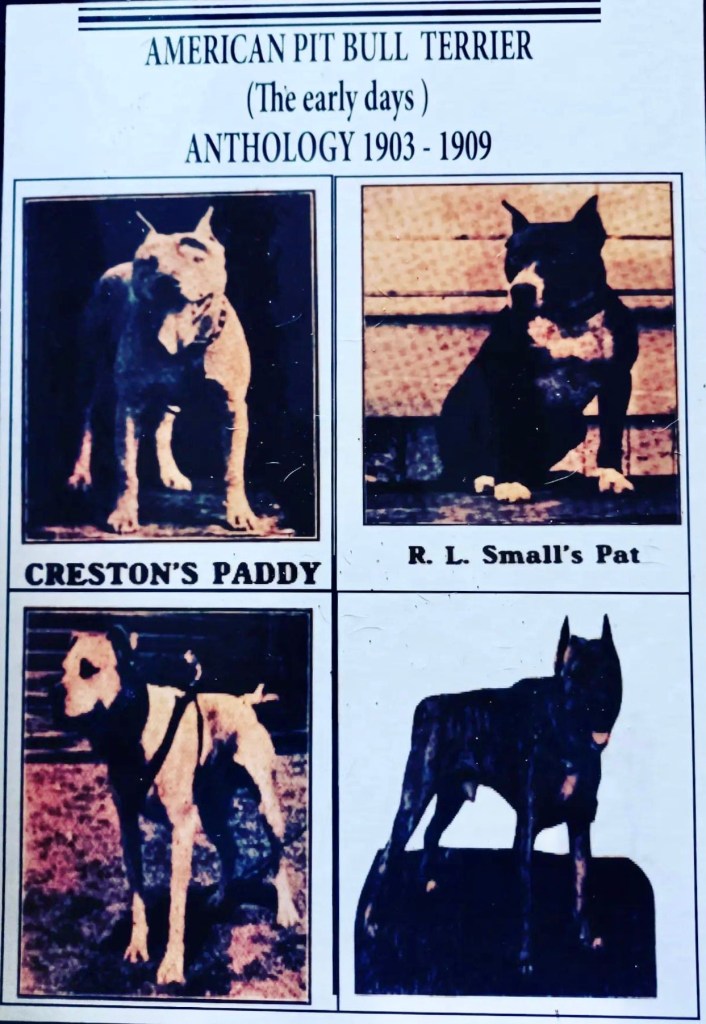

American pit bull terrier (the early days) anthology 1903-1909, hard cover, 130 pages,limited to 50 books, hand numbered & signed.

20 books left

A very rare and limited book, a collection of stories,articles,adds from the dawn of the breed basically, a must have for every pit bull fancier.

60 euros + shipping 😄

Sports and passtimes in old Ireland and England

George III (1738–1820), King of Great Britain and Ireland.

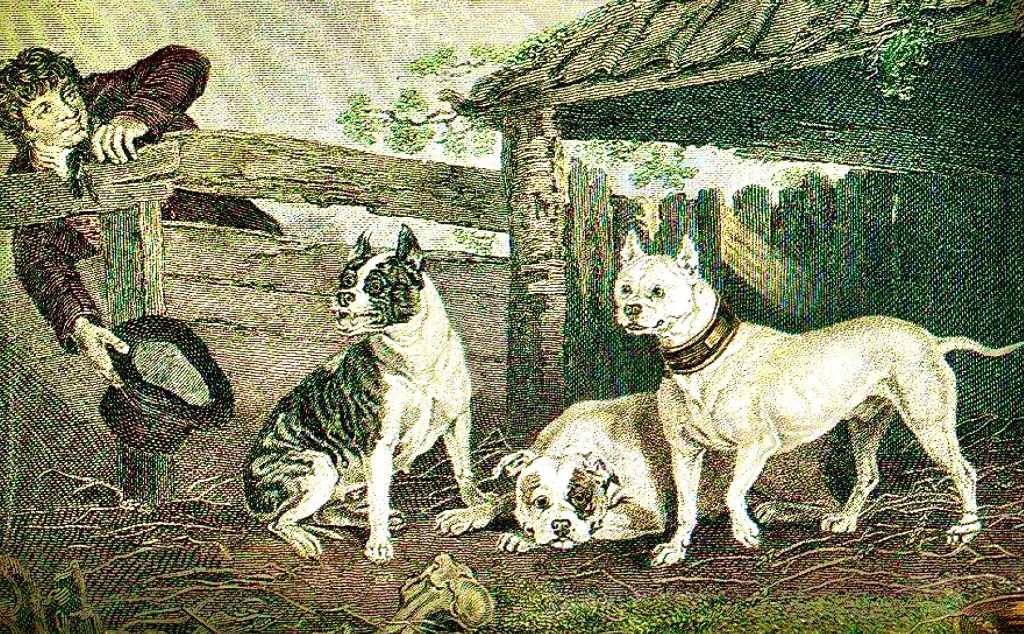

Somewhere around the year 1750, at that time cock fights were very popular and fights involving other animals came into fashion time and time again. These included fights between dogs and other animals – very often bulls – as well as straight dog fights. This was nothing new, as fights between animals of all species had been popular entertainment for people since ancient times. The fights themselves were legendary and reached the peak of their popularity between the years 1780 and 1835. These were also not fights to the death, since a good dog was an excellent means of livelihood for owners and bookkeepers alike. If anybody should feel shocked by this, they should consider the conduct of their own ancestors and draw on the implications to evaluate their own character. It wasn’t the dogs’ idea! Indeed, absolute tolerance of people was required of these dogs and they were important members of the family.

At the time, when the already much loved bulldog was not suited to a specialisation with emphasis purely on strength, the dogs’ lack of agility and speed was particularly felt. Attempts at crossbreeding therefore began in order to create a bold, strong, and agile dog. As always a number of experiments led to dead ends, but the crossbreeding of bulldogs with terriers turned out to be very promising. In different parts of Britain, different dogs were preferred. While weightier dogs were given priority in the north, in the Midlands, for example, smaller dogs were more suited. The desire to have a “proper” dog went through all social groups. From the rich nobility to innkeepers, craftsmen and miners all the way to breeders of rats and sewer rats for fighting. Do you wonder why I mention rats and sewer rats? Put very briefly and simply, the “combat” history of Staffordshires can be divided into three parts, fights with bulls, bears or other animals, to fights with other dogs and finally the “sporting“ extermination of rats and sewer rats. Such a fight was limited by time or the number of rats killed. A high-quality dog, for example, could kill 100 in the ring in five and a half minutes. It isn’t exactly a pleasant thought, but note than none of these dogs were ever intended to fight people. Injured dogs tended to be carted home, even in baby carriages. It is purely and simply today’s strange journalists and a few politicians who try to create the impression that these dogs are dangerous to people and use the word “combat” with an incredible amount of ignorance.

At that time the honourable Duke of Hamilton was considered by all to be the father of this “new breed“. King George the III (1760-1820), a supporter of the Duke, was on the throne. The duke bred a range of breeds in his kennels, including bulldogs and terriers, hunting dogs and fighting dogs. Together with his friend, Lord Derby, he dedicated his entire life to cock fighting, horse racing (particularly in Preston and Liverpool) and horses, and was a great friend of dog fights. Another of his close friends was the Prince of Wales, later King George IV, a great enthusiast of all kinds of fights. He was a prince who loved games, drinking, entertainment, and unbridled and wild horse rides. Simply the same as the majority of his peers at the time. These gentlemen would often meet at sporting events of the time and were avid gamblers. Cock fights and dog fights were also frequently held during horse races as an accompanying programme. They were certainly not in ruin as bets would often reach stakes of up to two or three thousand guineas. The Duke of Hamilton was certainly an expert of his day. After all, the future king later also acquired his dogs from the duke which can be seen in, among other things, a picture from around 1790 painted by artist George Townley Stubbs. The painting depicts the prince on a race horse, accompanied by two dogs with features with which we are very familiar.

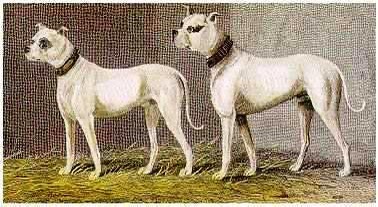

The Duke of Hamilton’s dogs were highly valued and rarely defeated, and the desire and prestige of other aristocrats was to acquire puppies of his dogs. The duke was not the only one who crossbred bulldogs and terriers. However, unlike others he made use of his experience of breeding racehorses. He worked systematically and tried crossbreeding distant and closely related crosses of bulldogs and terriers until he found his way to the result we know today. The foundation of these dogs was his own rearing in which he cultivated the breed somewhere around the year 1770. At the beginning, a light-coloured and fast bulldog also came from his kennel. And so his bull and terrier was born. Particularly famous dogs bred by the duke were Wasp, Child, Billy and Tyger. In a painting by H.B. Chalon depicting Wasp, Child and Billy, which at that time was owned by Henry Bonton (having acquired it after the death of the Duke of Hamilton in 1801) we can see their resemblance to Staffordshires of today. Female, Tyger was a perfect example of the new breed and His Majesty was so proud of her, that he commissioned a portrait of himself with her. All of the named dogs are ancestors of modern Staffordshires which is plain to see.

There are a number of theories regarding exactly how the breed came into existence in terms of the ratio of matings of a terrier and a bulldog and the creation of bull and terrier type dogs. Fortunately, the works of art of painters of the day can help us. Many significant painters from the period between 1780 and 1830 painted members of the aristocracy and other distinguished personalities with their dogs. A number of those dogs depicted, as I have already said, are direct ancestors of today’s Staffordshire Bull Terriers. Henry Alken was among the most important artists of the era and painted hunts for badgers and bears, motifs of bull baiting (the name of a hunting sport of the time, which had nothing to do with bears). They can be found, for example, in Alken’s work published in „National Sports of Great Britain” from 1820, which also includes one of the first depictions of a Staffordshire. Another famous painting is Crib and Rosa, in which Crib shows characteristics of Staffordshires, while Rosa appears rather like today’s bulldog. Stubbs painted the bull terrier in a position we can be proud of today: “Here I am, look at me!” The painting is dated 1812 and the resemblance with the previously mentioned female Wasp is so great that they were probably mother and son or other relatives. And we could go on and on in this way. Sporting Magazine from the era is another rich source of information.

M. M.

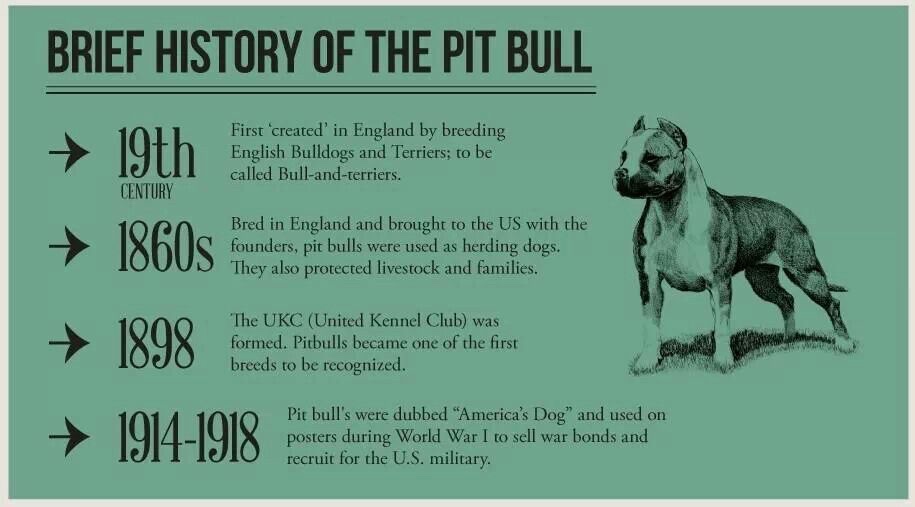

Bull and terrier, not to be confused with bull terrier.

Bull and terrier was a common name for crossbreeds of bulldogs and terriers in the early 19th century. Other names included mongrels and half-breeds. For thousands of years, dogs have been classified by use or function, unlike modern pets that have been bred to be show dogs and family pets. Bull and terrier crosses were originally bred as fighting dogs for bull and bear baiting and other popular blood sports during the Victorian era…. The sport of baiting required a dog with characteristics such as tenacity and courage, a broad body with heavy bones, and a muscular, protruding jaw. By crossing bulldogs with various terriers from Ireland and Britain, breeders introduced “game and agility” into the hybrid mix.

Little is known about the pedigrees of crosses between bulls and terriers or other crosses that arose during that period. Dog types and styles varied geographically according to individual preferences. Breeders in one area may have preferred a crossbreed with a higher proportion of terrier than bulldog. Some early anecdotal accounts indicate that bulldog was preferred to terrier over bull and terrier to bull terrier, probably resulting in at least half or more bulldog blood. The term Bull and Terrier has never been a true breed, but rather refers to a heterogeneous group of dogs that can include pure breeds involving different breeds as well as dogs believed to be crosses of those breeds. These crosses or hybrids are considered the forerunners of many modern standardized breeds.

In 1835 the various blood sports were banned, when enforcement of the blood sport ban began, the popularity of the original purebred bulldogs declined and a major change in canine genetics occurred. The appearance of some dogs was being modified by crosses to better suit their function. Not only did the appearance of dogs change, but also the terminology used to describe the various breeds and types of dogs, as recorded in ancient documents. Such changes began to cast doubt on the earliest known ancestors of the bulldog.

One example of how changing terminology over the centuries has led to confusion is the widespread misuse of descriptors. For example, mastiff is a common descriptor for all large dogs, which has created a shadow over the bulldog’s early origins. At one time the Alaunt was believed to be the probable ancestor of bulldogs and mastiffs, which came from Asia; others believed that bulldogs descended only from mastiffs.

Over the centuries, hybrid crosses of bulls and terriers have been labeled with various appellations, such as half-and-half, pit dog, bulldog terrier, and pit bulldog… The most popular name was bull-terrier, a name later applied to the breed that James Hinks was developing in the second half of the 19th century. There are also many paintings, texts and engravings created during or before this period that label the bull-and-terrier only as “bull-terrier.” Hinks was still developing his new bull terrier, nicknamed White Cavalier, which he presented at the Birmingham Exposition in May 1862.

The term pit bull terrier has sometimes been applied, although it was later used to name the American Pit Bull Terrier, a standardized modern breed. The term “pit bull” is a ubiquitous term that is often misused to infer that the pit bull is a bona fide dog breed, when in fact it refers to a heterogeneous group of dogs that can include purebred dogs of many breeds, as well as dogs that are supposed to be mixtures of such breeds. These types of descriptors vary according to recognized breeds and observers’ perspectives. Despite anecdotal misinformation and visual misidentification, dog owners, animal shelters, veterinarians, and the general public routinely use the term “pit bull” in informal and official documents as if it denoted a single recognized breed.

History

Bull and terrier hybrids were supposedly crossed with different varieties of bulldogs and terriers, the types of which depended on location. A 2016 genetic evaluation verified that bulldogs are descended from mastiffs, but also discovered the presence of pugs in the crossbreed. The evaluation, which looked at a particular group of English bulldogs, used DNA rather than pedigree to confirm that genetic diversity still exists. It also confirmed a substantial loss of genetic diversity in the breed due to a small founder population of about 68 individuals. The impact of targeted selection to breed dogs with specific physical traits has created artificial genetic bottlenecks.

In Ireland, the old Irish bulldog was used with several terriers and some sighthound/terrier crosses. In England there were several varieties, such as the Walsall, Cradley Heath and Darlastone types. Phil Drabble reported that among the various bull and terrier types, the Cradley Heath type was recognized as a separate breed to be called Staffordshire Bull Terrier. In the nineteenth century, the Walsall type was brought by immigrants to the United States, where it served as an important component for the genetic basis of the American Pit Bull Terrier breed, through such specimens as the Lloyd’s Pilot dog and the Colby lineage, which was heavily combined with Irish strains. The anatomy of the bull and terrier is the result of selective breeding for hunting, dog fighting baiting sports.

Descendants

In the “Popular and Illustrated Canine Encyclopaedia” (1934-5), edited by Walter Hutchinson, Major Mitford Price wrote: “The original Bull Terrier, or Bull-and-Terrier, as it was called then, bred for pit fights, looked much more like the Bulldog of that time than its terrier ancestors. The Bull-and-Terrier, as it was then called, was much more like the Bulldog of the time than its terrier ancestors: in fact, there are dozens of old engravings showing that the old Bulldog, as well as the Bull-and-Terrier, had the Bulldog’s unexaggerated (compared to the absurd modern standards) head and the terrier’s straight, longer legs. At the same time that the new Bull-and-Terrier appeared, Bulldog breeders began to breed their animals heavier and shorter, so that the Bulldog acquired a new type.

Six distinct breeds are descended from bull-terrier hybrids, five of which have been recognized by the American Kennel Club (AKC) in the following order: bull terrier, Boston terrier, American Staffordshire terrier (AmStaff), Staffordshire bull terrier, and miniature bull terrier. All five breeds have also been recognized by the Canadian Kennel Club (CKC) and the Fédération cynologique internationale (FCI). The American Pit Bull Terrier (APBT) is recognized by the United Kennel Club (UKC). The Kennel Club recognizes four of the breeds mentioned, but does not accept the AmStaff or APBT.

DNA analysis.

Geneticists can further refine the limited historical aspects of breed formation and the timing of hybridization. A 2017 whole-genome study suggests the following: “In this analysis, all crosses between bulls and terriers correspond to Irish terriers and date from the 1860s to 1870s. This corresponds well with historical descriptions that, while not identifying all the breeds involved, report on the popularity of dog shows in Ireland and the lack of veracity of studbooks, thus undocumented crosses, during this era of breed creation (Lee, 1894).”

Walsh also wrote about the Fox Terrier (or, rather, its half-breed ancestor), “The field fox-terrier, which was used to drive away the fox when it went ashore, was of this breed [bull and terrier].” The Fox Terrier is not only the offspring of the bull and terrier, but also of the Airedale Terrier, rat terrier, black and tan working terrier and most other hunting terriers. James Rodwell, in his book titled The Rat: Its History and Destructive Nature, describes that the great goal among the various breeders of bull and terrier dogs for vermin and rat hunting was to have them as similar as possible to the purebred bull, but at the same time to maintain all the external appearances of the terrier in terms of size, shape and color.

The terrier, used for hunting, is a strong and useful little dog, endowed with great stamina and courage and a nose almost equal to that of the Beagle or Harrier. Because of its superior courage when crossed with the Bulldog, like most vermin terriers, it was generally kept to kill vermin whose bite would discourage the Spaniel or Beagle, but would only make the terrier more determined to pursue them. ~ John Henry Walsh , The dog, in sickness and in health, from Stonehenge (1859)

James Hinks, a Birmingham breeder, is credited with helping to standardize the bull-terrier hybrid. Hinks introduced new blood, presumably Collie, to add length to the muzzle. His version was becoming a more simplified version of the bulldog-terrier hybrid while retaining substance. Hink’s son recounted that, early on, his father also used Dalmatians to create the Bull Terrier’s striking all-white coat. Others have suggested that Hinks straightened out the bulldog’s tendency to have crooked legs by adding Pointer, or perhaps Greyhound, blood. Hink’s son recalled, “In short, he became the old civilized fighting dog, with all his roughness blunted without softening it; alert, active, brave, muscular, and a true gentleman.” Hink’s earliest Bull Terriers were white, which gave rise to congenital sensorineural deafness (CSD), a genetic condition linked to coat color phenotypes in English Bull Terriers with genetic variations beyond coat color. The appearance of the Bull Terrier continued to change over time, and by the 20th century its egg-shaped head had become more noticeable and soon became standardized along with the various colors that were introduced.

Mike Morabito

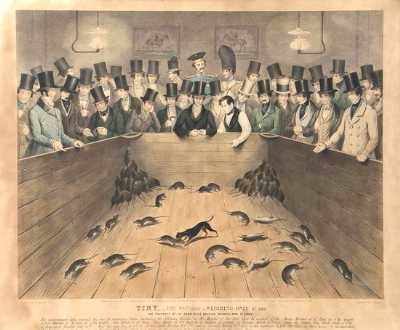

Rat baiting. P. 1

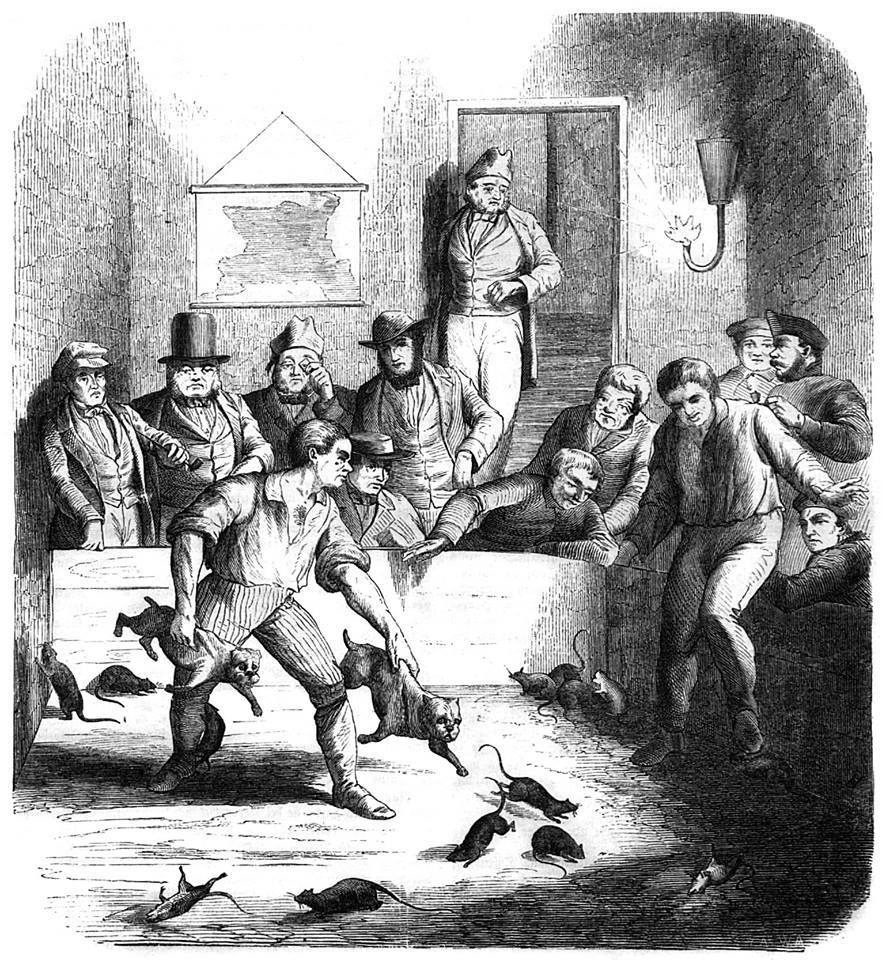

Rat baiting is a blood sport, which involves placing captured rats in a sunken pit or other enclosed area surrounded by spectators, and then betting on how long a dog, usually a terrier, takes to kill them by taking rats in its mouth and shaking them to death. Often, two dogs competed, with the winner receiving a cash prize. It is now illegal in most countries.

History

In 1835, the Parliament of the United Kingdom implemented an act called the Cruelty to Animals Act 1835, which prohibited the baiting of some animals such as the bull, bear, and other large animals. However, the law was not enforced for rat baiting and competitions came to the forefront as a gambling sport. At one time, London had at least 70 rat pits.[1]

Turnspit Quakers Alley

Atmosphere

James Wentworth Day, a follower of the sport of rat baiting, described his experience and the atmosphere at one of the last old rat pits in London during those times.

This was a rather dirty, small place, in the middle of the Cambridge Circus, London. You went down a rotten wooden stair and entered a large, underground cellar, which was created by combining the cellars of two houses. The cellar was full of smoke, stench of rats, dogs, and dirty human beings, as well. The stale smell of flat beer was almost overpowering. Gas lights illuminated the centre of the cellar, a ring enclosed by wood barriers similar to a small Roman circus arena, and wooden bleachers, arranged one over the other, rose stepwise above it nearly to the ceiling. This was the pit for dog fights, cockfights, and rat killing. A hundred rats were put in it; large wagers went back and forth on whose dog could kill the most rats within a minute. The dogs worked in exemplary fashion, a grip, a toss, and it was all over for the rat. With especially skilful dogs, two dead rats flew through the air at the same time …

Rules

The officials included a referee and timekeeper. Pits were sometimes covered above with wire mesh or had additional security devices installed on the walls to prevent the rats from escaping. Rules varied from match to match.

In one variation, a weight handicap was set for each dog. The competing dog had to kill as many rats as the number of pounds the dog weighed, within a specific, preset time.

The prescribed number of rats was released and the dog was put in the ring. The clock started the moment the dog touched the ground. When the dog seized the last rat, his owner grabbed it and the clock stopped.

Dogs used in rat baiting varied in size.

Rats that were thought still to be alive were laid out on the table in a circle before the referee. The referee then struck the animals three times on the tail with a stick. If a rat managed to crawl out of the circle, it was considered to be alive. Depending on the particular rules for that match, the dog may be disqualified or have to go back in the ring with these rats and kill them. The new time was added to the original time.

A combination of the quickest time, the number of rats, and the dog’s weight decided the victory. A rate of five seconds per rat killed was considered quite satisfactory; 15 rats in a minute was an excellent result.

Cornered rats will attack and can deliver a very painful bite. Not uncommonly, a ratter was left with only one eye in its retirement.

Mike Morabito

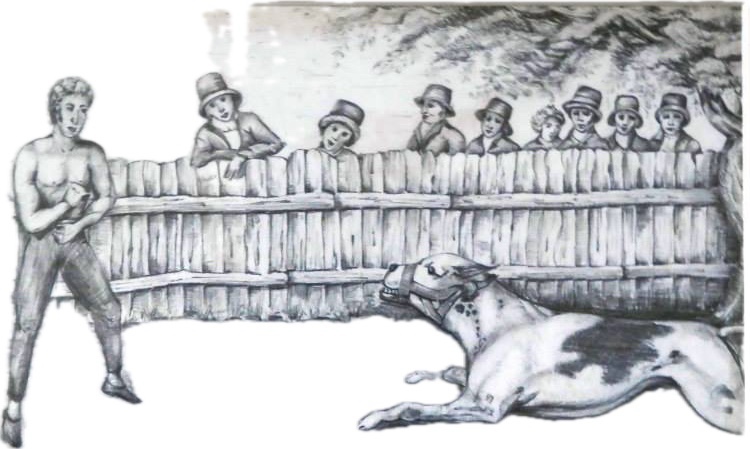

HUMAN – BAITING WITH DOGS

Human – baiting is a blood sport involving the baiting of humans.

There are at least three known documented cases of human-baiting, all of which occurred in England in the19th century.

The Sporting Magazine, vol. XVIII, documented a fightbetween parties labeled simply the Gentleman and the Bull Dog. The Sporting Times also reported on this fight, which occurred in 1807. The story illustrates the outcomeof a large, mastiff – like dog charging its opponent. Despitethe handicap of a muzzle, the dog was the winner.

A fight between a man and Bull Dog took place some time ago to settle a bet. With its first charge the Bull Dogalready succeeded in throwing and pinning its opponent. Although the dog’s jaws were nearly closed by a muzzle, itsucceeded in sinking its teeth into the man’s body. Had thedog not been pulled away immediately, it would havedisemboweled the man.

Physic and Brummy, An Evening at Hanley

On 6 July 1874 the Daily Telegraph published an article, written by James Greenwood, in which he reported on 25 June 1874 to have witnessed a fight between a man and a dog. Greenwood recounted the tale in his 1876 book, Low-Life Deeps, in the chapter called In the Potteries. OnJuly 11, 1874, The Spectator published an article calledThe Dog-Fight at Hanley that described the circumstancesof the brawl.[1]

The fighter, named Brummy, was a middle-aged dwarfabout 4.5 feet (1.4 m) tall, with oversized features, and bowed legs. He had apparently agreed to fight the dog fora bet, on his theory that no dog “could lick a man”. Hisopponent was a white bulldog named Physic. Held by itsguardian, the dog apparently did not bark, but was excitedto the point where tears ran from its eyes. The fight, watched by an audience of about 50, occurred at an old innat Hanley, Staffordshire, in a large guest room, itswindows closed and its floor covered in sawdust, with thering cordoned off by a line.

During the fight Brummy was bitten deeply several times on his arms, and the Bulldog was dealt several heavy blows to the head and ribs. After ten rounds the Bulldog’shead was heavily swollen, it had lost two teeth, and one of its eyes was closed. The fight lasted until round eleven when Brummy knocked the dog out.

This story was reported on by The New York Times, which stated that the story is probably false, though notingthat the Daily Telegraph insisted on its veracity.[2]

East End Club

In 1892, another human-baiting occurred between thehuman combatant James Oxley and a fighting dog namedCrib. The following is extracted from a contemporaryreport:[3]

An arbite (man and dog fight) took place in an East EndClub.

The match was that James Oxley, a man well known in theneighbourhood of Shoreditch, would stall off for thirty-minutes a fighting dog called ‘Crib’ owned by Robert Green. The match came off not many yards from theBritannia Theatre, Hoxton and excited considerable interest amongst those in the know. Some of the prominentpeople, who brought about this sickening match, wheninterviewed, stated that for twenty-one minutes Oxley keptthe dog off by using his fists. But, at one moment, the dogmade a desperate effort to get past the man’s guard and didand jumped over his left shoulder, wheeled round and fastened on the man’s right ear, and dragged him to theground. As soon as it was possible, the dog was chokedoff, but the upper part of Oxley’s ear had disappeared.

RAT BAITING P.II

Rat-catcher

Before the contest could begin, the capture of potentially thousands of rats was required. The rat catcher would be called upon to fulfill this requirement. Jack Black, a rat catcher from Victorian England supplied live rats for baiting.

Technique

Faster dogs were preferred. They would bite once. The process was described as “rather like a sheepdog keeping a flock bunched to be brought out singly for dipping,” where the dog would herd the rats together, and kill any rats that left the pack with a quick bite.

The ratting dogs were typically working terrier breeds, which included the bull and terrier, Bull Terrier, Bedlington Terrier, Fox Terrier, Jack Russell Terrier, Rat Terrier, Black and Tan Terrier,[5][6] Manchester Terrier, Yorkshire Terrier, and Staffordshire Bull Terrier.[7] The degree of care used in breeding these ratters is clear in their pedigrees, with good breeding leading to increased business opportunities. Successful breeders were highly regarded in those times. In modern times, the Plummer Terrier is considered a premiere breed for rat catching